The Bonus Book of the Week is “Ian Fleming, the Man Behind James Bond” by Andrew Lycett, published in 1995.

Born in May 1908 in Mayfair in England, Ian Fleming had a childhood befitting his place in an elitist, wealthy family. However, his older brother Peter was the favorite. Fleming was sent to boarding school at six years old. Then it was off to Eton and Sandhurst. His father was killed in WWI when he was nine.

Fleming’s strong suit was sport, not academia. He failed both to become a military officer while in training, and the diplomatic-service entrance exam. This, after this wild child was sent to a language school in Switzerland and a finishing school in Munich. Then a school in Geneva.

In the early 1930’s, at wit’s end, his mother helped him go to work for Reuters. But she prevented him from getting married by telling his employer to deny him permission to marry– something it had the authority to do in those days.

In 1934, when he followed in his father’s footsteps by entering the lucrative banking field, he began to lead a charmed life. He took up gambling, golf, tennis, skiing, carousing, and sowing his wild oats. He played well with others and made lots of valuable contacts. Even so, banking was really not his thing either.

Although lacking the bent of a student, Fleming’s thing was bibliophilia. He developed the concept of amassing a library which was responsible for worldwide technological or intellectual progress since the year 1800– “books that made things happen.” The collection, spanning more than four hundred volumes from more than twelve nations, published from the 1820’s through the 1920’s, improved humanity and changed the world.

Through centuries, people have done so, too. They have been muckrakers, whistleblowers, dissidents and activists, and have been called heroes and martyrs. Most of them, even the famous ones, who risked their lives to counter political ideology that was oppressing a large number of people, are deserving of high praise.

The most recent examples of countless such individuals who saved countless lives include those who acted courageously during the Holocaust; two who come to mind are Raoul Wallenberg and Oskar Schindler. However, they need not have directly saved lives to have made an impact, though they made serious sacrifices for their causes: Mahatma Gandhi, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Andrei Sakharov, Daniel Ellsberg, Vaclav Havel, Aung San Suu Kyi, Nelson Mandela, Edward Snowden, etc., etc., etc.

Ralph Nader is exceptional in this regard– he saved lives but did not risk his own life. In medicine too, there have been plenty of such individuals, like Alexander Fleming (no relation to Ian). However, politics is a more widespread subject of discussion and there are no barriers to entry. Therefore, more individuals’ names in politics enjoy longer historical recognition. Also– medicine is governed by politics because it’s a matter of life and death. Politics is all about tribal unity and public relations. Image management is all it takes to acquire a political footnote in the history books. Some individuals have been too power-hungry to care about their do-good legacies.

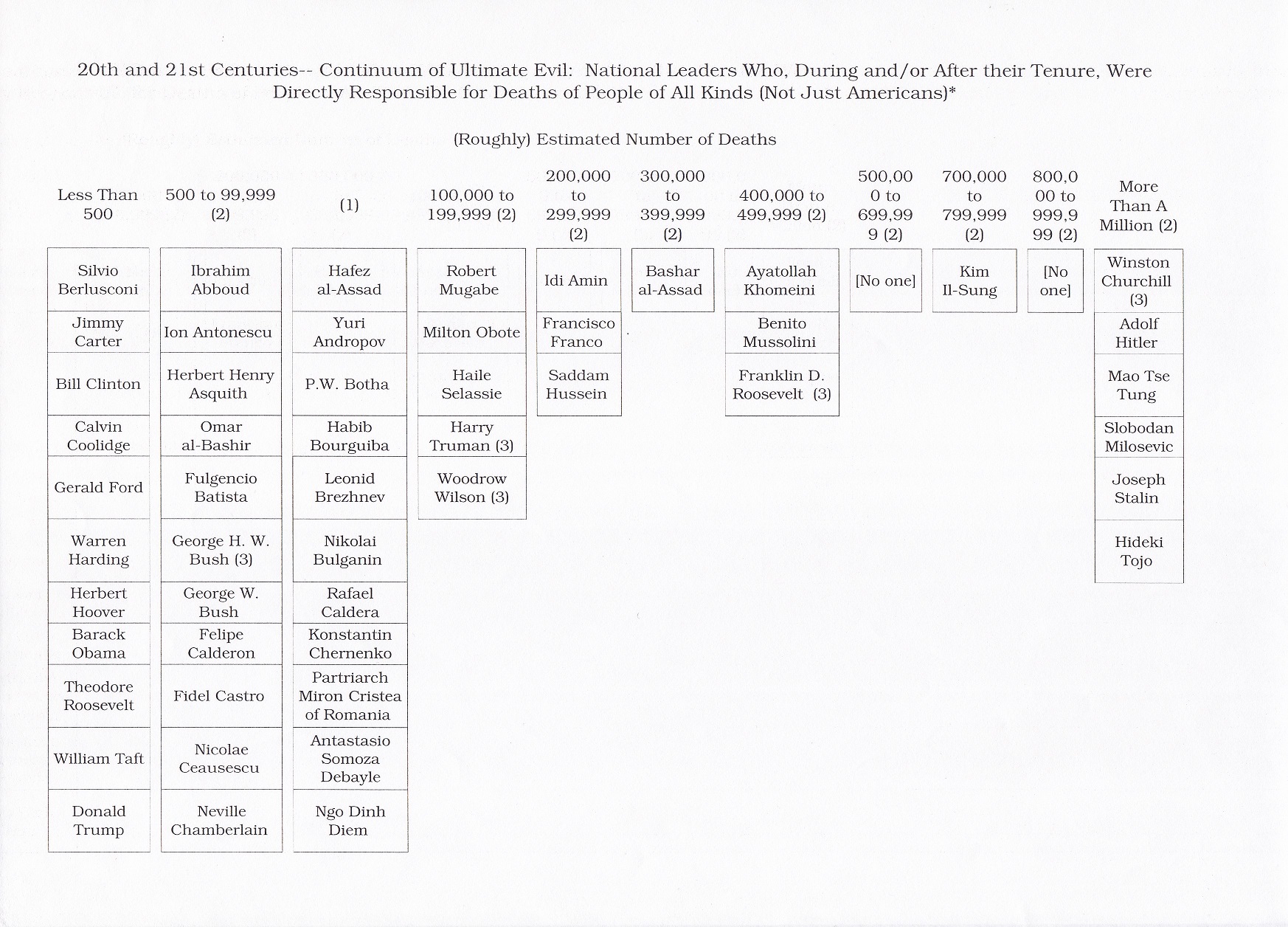

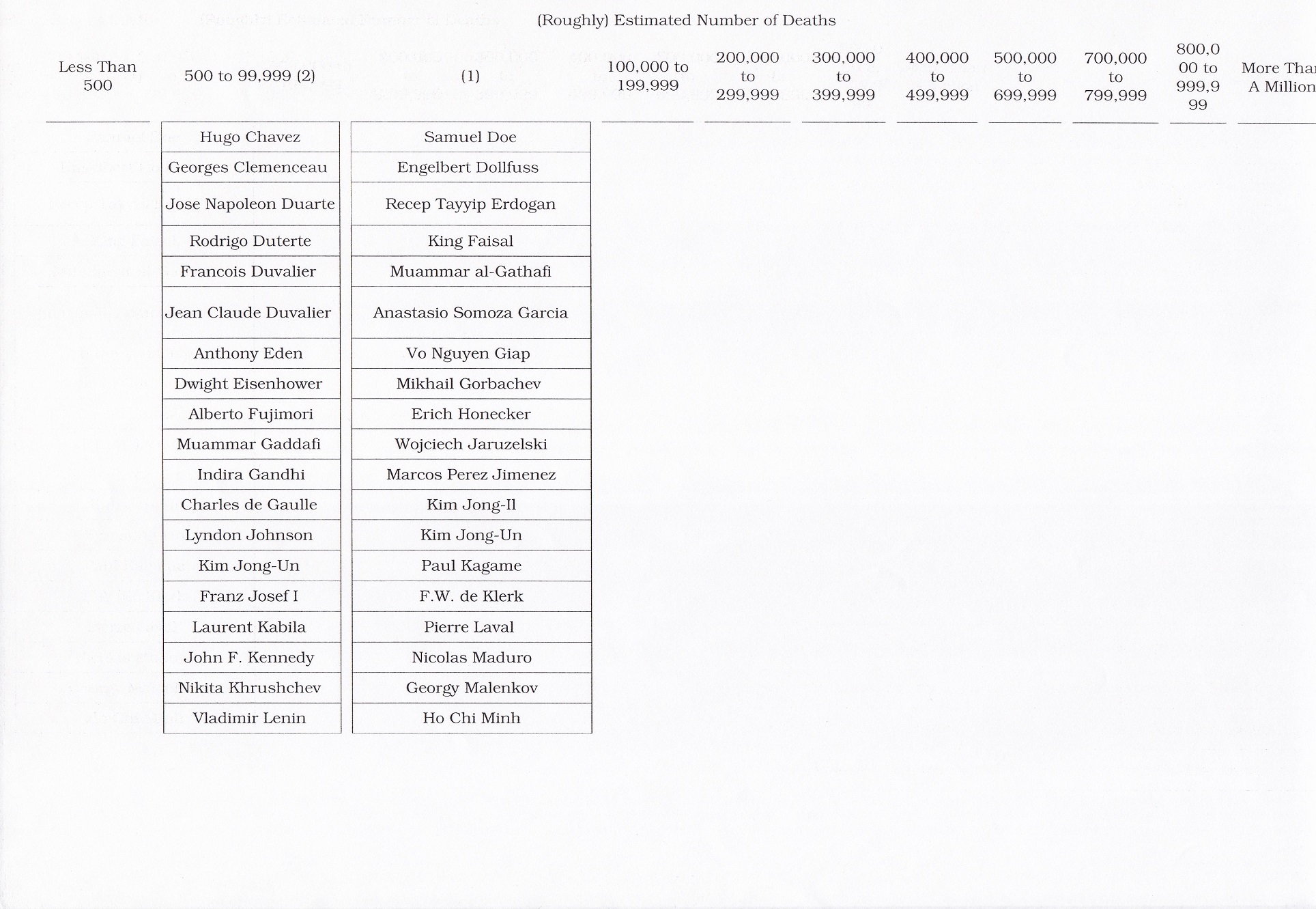

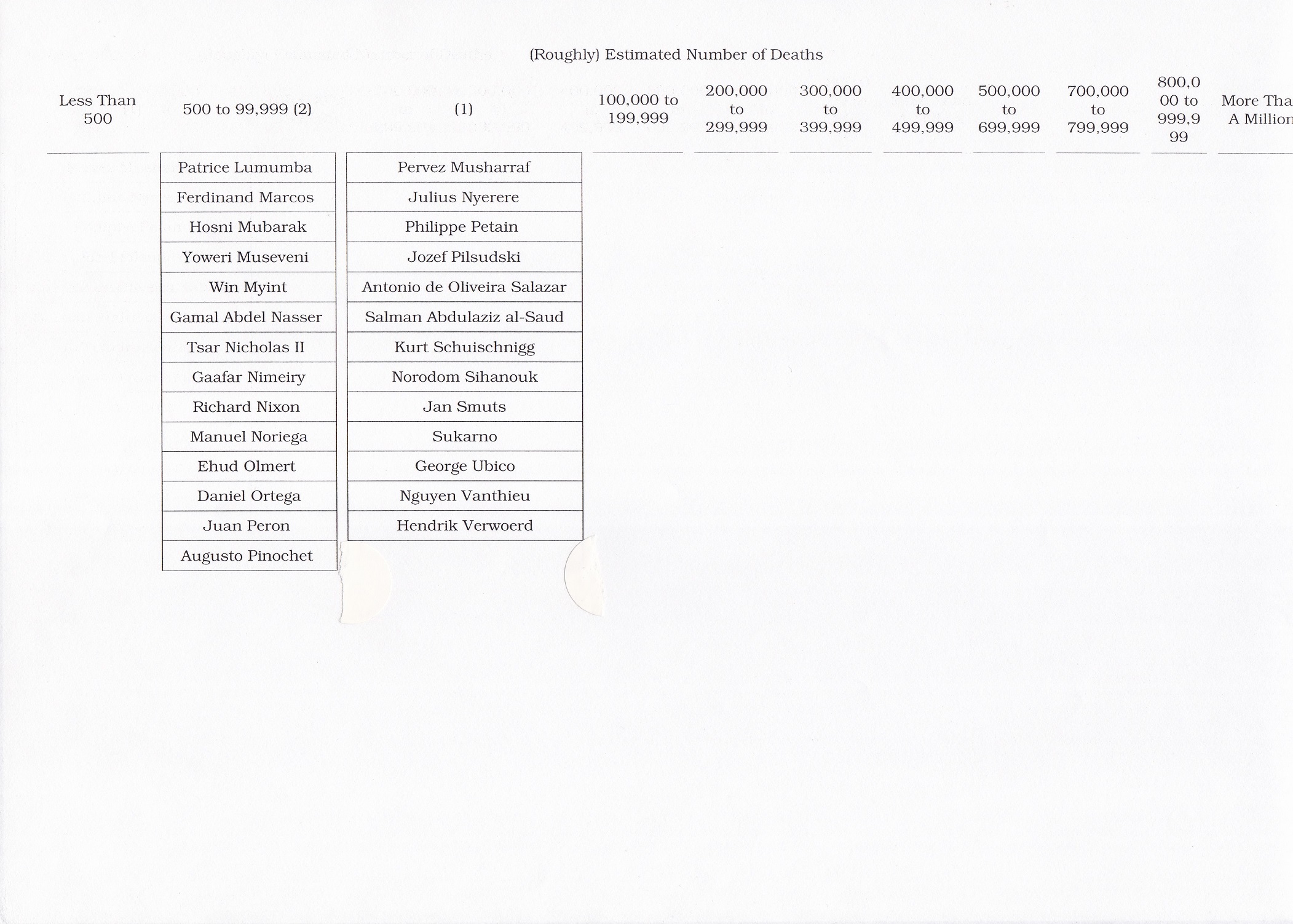

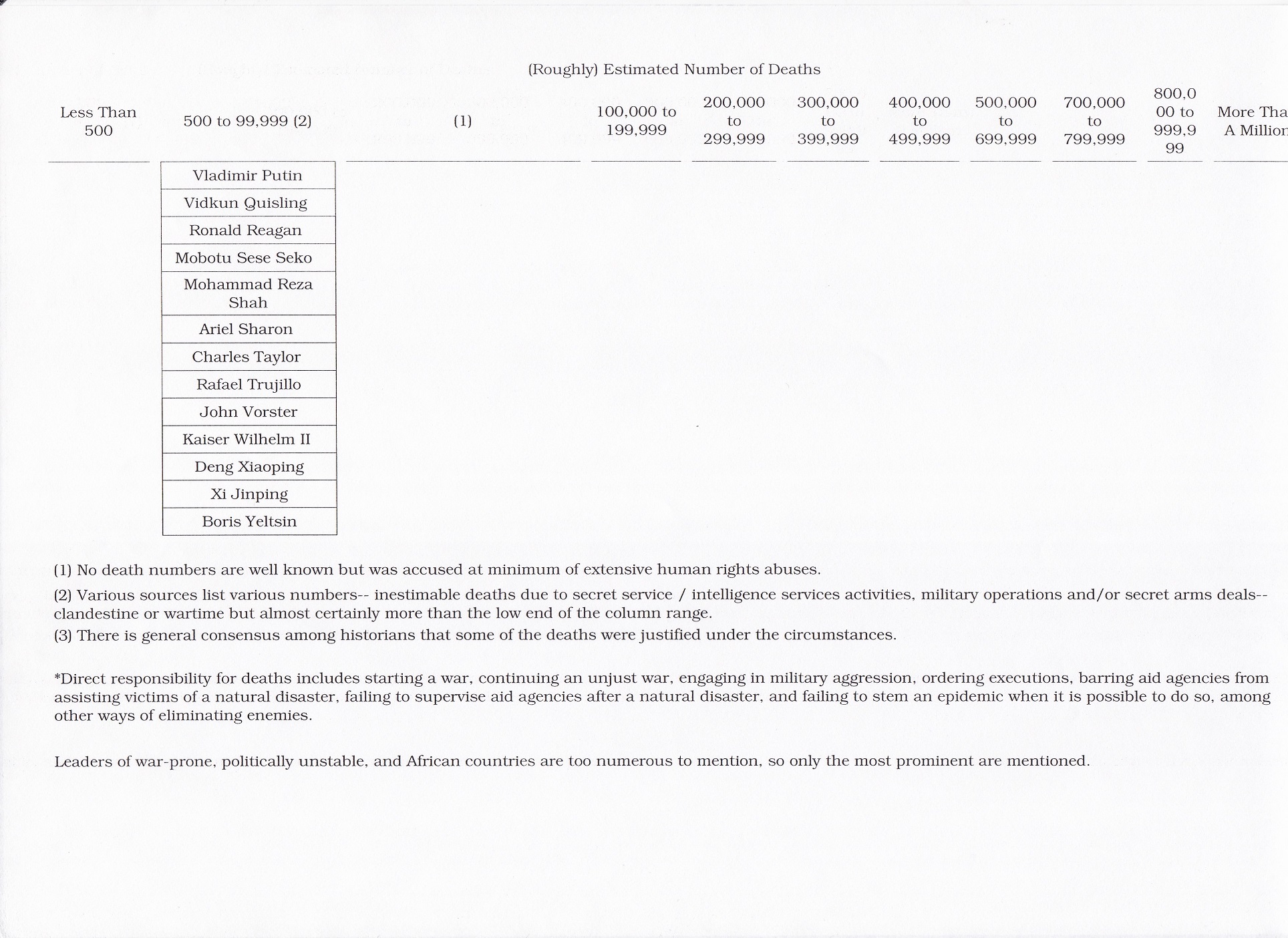

That’s the flip side of the coin– evil. Individuals’ evil can be quantified– by the number of deaths for which they are directly responsible. Comparing politicians who have made unfortunate remarks or have engaged in unfortunate actions or behaviors, to Hitler– is usually an invalid comparison. He was a genocidal maniac. The true comparisons to Hitler and others are displayed below in alphabetical order by last name (footnotes 1-3 are at the bottom of the fourth page).

Anyway, Ian Fleming played bridge with a literary social set. Yet, at 28, when he finally moved out of his mother’s home, he was still a megalomanaical, hedonistic schoolboy, a smoker and drinker.

The year 1939 saw him begin to engage in his true passion– intelligence gathering (and collecting weaponry), for the British government. He found subversion, sabotage and clandestine warfare so exciting.

After the war, he bought a vacation house which he called Goldeneye in Jamaica in the Caribbean, and became a journalism manager for the Sunday Times in London. He supervised spies who posed as journalists. They cranked out propaganda his way. “First drinks of the day were served at eleven in the morning.”

By 1950, Fleming’s mother had moved to Cannes for the purpose of tax evasion. Less than two years later, Fleming had written his first novel, Casino Royale. The main character was a Renaissance man called James Bond who engaged in gambling, espionage and economic sabotage. He was all that men wished they were.

Nonetheless, his publisher in America requested that he tone down the sexual-sadism-and-masochism language for the good of book sales there. His stories tended to contain sicko characters who were improbably good at escaping from impossibly bad situations– designed to shock the reader and offend his sensibilities with their extreme goings-on.

Fleming made frequent visits to the United States over the years. He astutely concluded that Walter Winchell, Joe McCarthy, and J. Edgar Hoover were evil. Fleming had a large, diverse social set that included Noel Coward and Jacques Cousteau. They gave him ideas for his novels.

Read the book to learn about: the intellectual-property legal disputes among the various entities handling Fleming’s career; his family life; about the extensive research (including personal travel to experience various subcultures) he did when writing; and why reviews on his books suggested that he had various psychological issues such as a low level of maturity, sociopathic tendencies and sexual deviance.